I am now delighted to be able to report that I have evidence to support this theory. I don't normally quote so extensively from articles readily available elsewhere on the web but this is so relevent I feel I have to. In an interview with Random House, writer Samuel Delaney says:

I am now delighted to be able to report that I have evidence to support this theory. I don't normally quote so extensively from articles readily available elsewhere on the web but this is so relevent I feel I have to. In an interview with Random House, writer Samuel Delaney says:One of the glories of the late sixties comic book field was what were then called "relevant comics." In reaction to the freedom and daring of the then-burgeoning "underground comics," commercial comic books of the era began to take on far more mature themes and problems--social topics that had some punch: racism, child abuse, drugs, and what-have-you. The leading writer in this movement was Denny O'Neil and the leading artist, Neal Adams. It was an exciting moment in comics. The New York Times Magazine even devoted a Sunday cover article to them.

Well, five or six years before that, Wonder Woman's writers had found themselves with the "Superman problem": Because she was so powerful, none of the villains could really offer any resistance, and Wonder Woman--nee Diana Prince--had been reduced, for several years, to Saving the Entire Earth from the Blue Meanies of Mars, or other equally mindless adventures. So, finally, the editors had done the only sane thing: Most of her super-powers had been taken away, and she was now just you ordinary black-belt karate expert and generally super-brave kick-ass heroine type--a sort of female Steven Seagal. She was still pretty damned heroic. Instead of the flag bra and blue bikini briefs, she wore a white karate gee with a black belt. Certainly it made it easier to come up with reasonable plots for her, and alone made it possible for the plots to have some relevance to the real world.

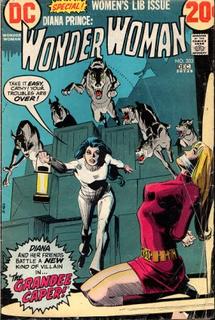

Once the new relevant comics came along, they editors decided an area they wanted to tackle was women's problems. By that time Denny was editing Wonder Woman; he asked me to write a series of scripts for Wonder Woman that would touch on problems of actual women. (You might have thought, if they were really serious, they would have gotten a woman writer. But that, I suppose, was a bit too radical.) I came up with a six-issue story arc, each with a different villain: the first was a corrupt department store owner; the second was the head of a supermarket chain who tries to squash a women's food co-operative. Another villain was a college advisor who really felt a woman's place was in the home and who assumed if you were a bright woman, then something was probably wrong with you psychologically, and so forth. It worked up to a gang of male thugs trying to squash an abortion clinic staffed by women surgeons. And Wonder Woman was going to do battle with each of these and triumph.

Well, we only through two issues--and the first was a matter of writing Wonder Woman out of the last adventure she was in and getting back into her Lower East Side Neighborhood, which is where Diana lived by then anyway.

One day about six weeks after I had come on board, Gloria Steinem was being shown through the D.C. offices. Proudly they showed her the new Wonder Woman. Steinem hadn't looked at a Wonder Woman comic, however, since she was twelve. Immediately she exclaimed: "What happenned to her costume? How come she isn't deflecting bullets with her magic gold bracelets anymore and tying people up with her magic lasso?" Steinem didn't get a chance to read the story of course. But she complained bitterly: "Don't you realize how important the image of Wonder Woman was to young girls throughout the country?"

She had a point, I admit.

But, a day later, an edict came down from management to put Wonder Woman back in her American-flag falsies and blue bikini briefs and give her back all her super powers. Well, that's what happened--and she went back to Saving the Entire World from the Blue Meanies of Mars . . . There was no way I could work those in with the relatively realistic plot lines I had devised. So my stories were abandoned, and I was dumped as a writer--and Wonder Woman never did get a chance to fight for the rights of a women's abortion clinic.

It's a case of the world being over-determined--and over-determined in some destructive ways. But Steinem had no idea of the stories her chance comments were used to scuttle.

I think he may be exaggerating the time period involved a little for dramatic effect, and he seems unaware of Steinem's subsequent WW related activity. It seems a little hard to believe that Gloria Steinem could have caused the direction of the comic to be so radically changed in a single day, with a "chance comment", unless her influence at DC was far greater than anything I've found anywhere else has suggested, or it had already been decided to make this change. Her Wonder Woman related activities (the MS. cover and the reprint collection) always suggested to me a campaign to raise support for the classic Wonder Woman image. There would have been no need to come on so strongly if the publisher had immediately agreed to her suggestion.

What does support Delany's claim here is that however long it took for Steinem to persuade DC to change direction on the comic so radically, the actual change was implimented in a very short space of time, and with no warning. Issue #203 is entirely absent of any hint of change, even including a "next issue" box carrying on the current plot, so for that all to be changed after the issue was sent to the printers must have left a very short time indeed to create an entirely new comic. I can't help wondering how much of the art was completed on the original version and what became of it. And it makes me think that perhaps the reason they brought back Kanigher to write it was not just his experience on the title, but also because of his famed ability to produce at very short notice.

Delany is correct in essence, though. Her interest in Wonder Woman was entirely superficial, and once her goal was achieved she moved on without a backward glance to see what effect her interference had caused.

4 comments:

I'm wondering if part of the abrupt dismissal was also d due to A) fear of invoking controversy from or moral qualms over the abortion scenario on part of the editors and B) the fact that Samuel R. Delany's scenarios sound preachy and dead boring, even for "relevant" comics.

According to Gloria herself, in her lengthy introduction to the reprint volume she produced in 1972, she wasn't expecting the change to occur so fast. In fact she talks about looking forward to Wondy getting her star studded knickers back the next year in 1973.

At the very least this shows that she had time to produce the book between the time she got interested in Wonder Woman and the time it was revamped, so the whole "next day" scenario seems like more of a compression of events on Delaney's part.

I don't think he's deliberately lying, but you tend to edit out the dull periods between interesting events unconsciously as time goes on.

This is always such a great bunch of posts. You really need to have it show up on the Comic Weblog Update.

The abortion issue probably never would have seen print, Steinem or no Steinem. It's a third rail for comics now, outside of Vertigo/MAX maybe.

It is a shame that Delany didn't have more time to unwind his ideas, though.

Post a Comment